One of my regular responsibilities at my new job at the Credit Union is coaching developers, engineers, sdets and QA folks. Today, I got to be involved in three different coaching sessions that all had unique subjects and discussion points.

Session 1: How to get to Senior – Developing Expertise

This is a fairly common situation. A developer wants to go from Software Developer to Senior Software Developer.

The process of making Senior Software Developer generally comes down to adding more responsibility and influence to your day-to-day job. To get to a senior role, you can do one of the following:

- Take on a team lead role. In this case, you are the point person and responsible for more of the project work itself. You T-shape your skill set, but become the primary point person for the whole project.

- Take on a manager role. In this case, you’re trying to mentor and grow the skills of the folks around you. You may not be directly responsible to all the functions in the project, but you help and mentor those folks around you.

- Take on an expert role. In this case, you target getting deeply technical and specialized. Your plan is to become a known leader and expert on a particular technology.

The developer in question was interested in learning more about this third pattern of developing her expertise, and what it would take to continue that progression. She expressed interest in web user interfaces with Angular, and spent the session showing me what she had learned and worked on, and where she was going next.

To coach, sometimes you just need to be the accountability buddy.

Session 2 : Whose Design is Right?

In this session, a team of software developers had some questions about the nature of their solutions. They did not agree about the approach to a problem, and this particular session was with one side of that argument.

Side note: I love these sorts of discussions. Folks getting passionate about the way they choose to solve a problem is WONDERFUL.

The best part is that there was not a clear winner in the design of the application itself. They were different designs, to be sure, but they each had technical merits that could very easily be seen.

At the core, this one came down to coaching back to the engineering. The crux of the problem was that there was no data proving one solution better than another. The quantitative features of the respected solutions had not yet been tested, and that was the end state I coached towards here.

If your design is better, prove it with data. Otherwise, GTFO of the way.

Session 3 : SDETs in the Credit Union

Initially, this one was setup to be a discussion about how to write code to use a Windows Application automation tool (Selenium with WinAppDriver), but after the first session, it was apparent many of the SDETs present already had a lot of experience with those libraries. There were four SDETs and one analyst in this session, so it became a larger discussion about the nature of testing. We started collaborating on ideas about the about the best ways we could automate some of the harder tests to deal with.

Finally, it came down to discussions about the AAA pattern of testing, the kind of test code we wanted across the org, and even some of the difficulties in teams where SDEs and SDETs have a combative relationship.

Coaching engineers is exhausting and inspiring all at once. It was a great day, and I feel blessed to be able to do it!

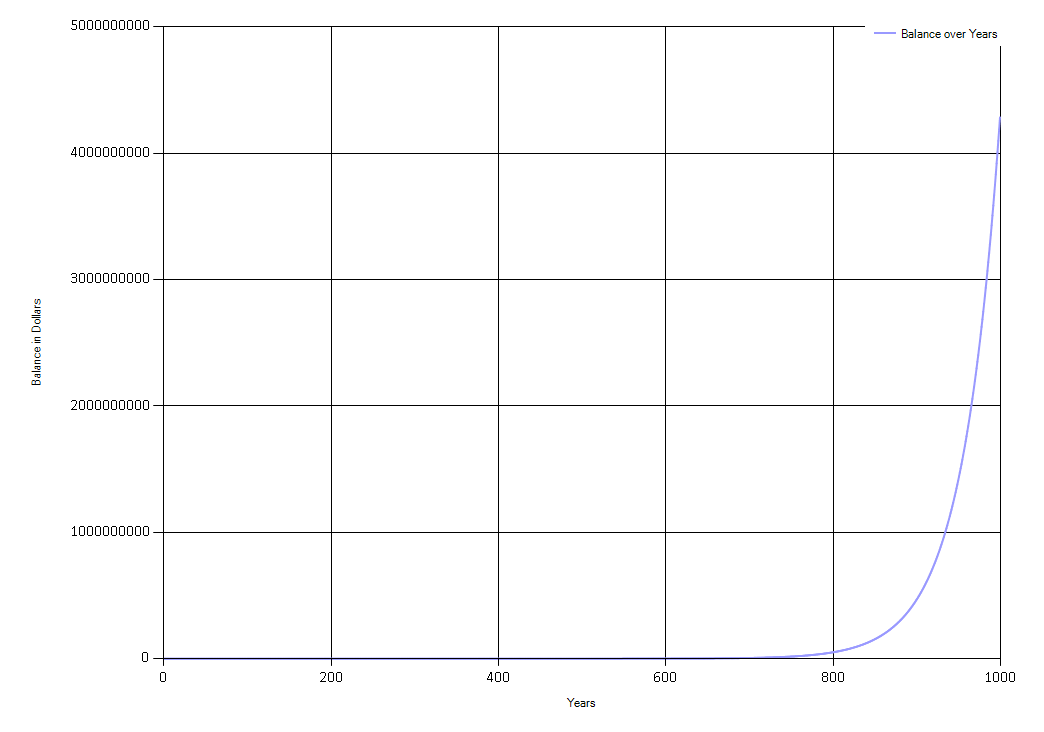

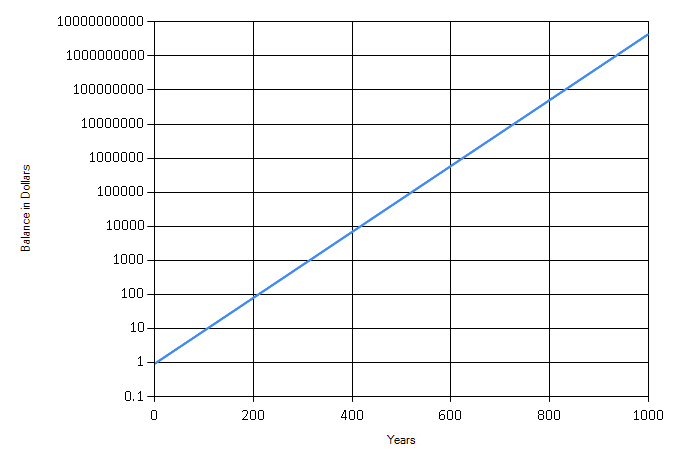

It looks like Fry’s bank account doesn’t get interesting until about 300 years or so. Still, compound interest is a wonder, despite

It looks like Fry’s bank account doesn’t get interesting until about 300 years or so. Still, compound interest is a wonder, despite